Southern

Pacific

8799

The Camera Car

Robert

J. Zenk

Mike

Minor Photo

|

Machine Age meets Space Age.

SP 9010 owes its survival to a groundbreaking late Sixties program by the Southern Pacific railroad: the creation of the first land-based full-motion locomotive cab simulator for crew training.

Why a simulator? Traditionally, engineers would train their firemen by allowing them to run trains and gain experience. There were many variables with this time-tested process, not the least of which was the bending of regulations, and the whims of engineers who may or may not have personally cared for their fireman, and vice-versa.

In the forward-looking, MBA-driven railroading of the 1960s, management began seeing this procedure as both archaic and a potential liability. SP also regularly plied its stockholders and shippers with advertising messages that the Company was at the cutting edge of transportation and communications, and this program carried built-in bragging rights. The U.S. was also embracing the Computer Age, and simulator technology had advanced greatly from its origins in World War 2 Link Trainers for pilots.

Wikipedia

Commons

|

SP was not alone on the pioneering path to a Locomotive Simulator; the competing Santa Fe was in parallel development and deployment of a rail-based Crew Training Simulator -- including a Camera Car of their own -- developed by another prominent aerospace firm, Singer-Link.

Yes, that 'Link.'

Bob Zenk Photo

|

(More about the Dueling Simulators in the APPENDIX following.)

SP 9113 Escapes the Torch.

The simulator technology of the time required the use of filmed and projected background plates of the track ahead - 'OTW', or "out the window" in simulator terms. To shoot that motion footage, a suitable camera platform was required.

All of the USA Krauss-Maffei locomotives were on borrowed time in late 1968; Southern Pacific had pulled the plug on the diesel-hydraulic experiment earlier in the year. Locomotives would operate until they experienced a major sidelining failure. SP 9113 was among the last of the soldiers, but finally toasted the number nine cylinder assembly of her forward Maybach V-16. It was a fatal injury. SP 9113, the former SP 9010, was stricken from the locomotive roster on September 18, 1968.

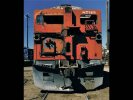

Shortly after, this forgotten foreigner was chosen as a rolling chassis for the Simulator Project. Here, we see work beginning on the stripping of front end parts in late 1968 -- say, that's a bit of deja vu of how the locomotive looked when the Pacific Locomotive Association acquired it forty years later!

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Why Pick a Dead KM?

Official reasons for the choice of one KM in particular haven't surfaced yet. Among the foremost recommendations likely are a.) it had been written off the tax schedule, b.) it was nearby -- the scrap line was near the General Shops -- and c.) it was not valuable for trade-in.

SP stockholders could also take comfort in the notion that their expensive German locomotive experiment was still returning service to the Company. But why was the former 9010 chosen over any of her other dead-line companions? Maybe as simple a factor as having six good wheels with plenty of tread.

There were a couple other advantages to choosing a KM: the operator's cab was high, the better to clear the Cardan shafts and other hydraulic propulsion machinery. That placed it well above the new camera box, which was high enough to for operators to stand up while presenting a camera level that was close to an EMD cab's eyeline. And the forward radiator area was easy to clear of relatively light auxiliary equipment while still maintaining overall weight balance: not so easy with a domestic diesel's heavy generator and prime mover.

SP9010

Collection

Bob Zenk |

SP 9010 Collection Bob Zenk |

Maybe someone at SP also had a secret desire to preserve a KM. So far,that's unsubstantiated!

Aero Tech Meets Hollywood.

Simulator technology was born of aviation, and SP's program was developed in cooperation with Conductron-Missouri, a subsidiary of McDonnell-Douglas. That firm also contracted to develop the Apollo moon shot simulators. (We like to say that the moon landing saved our KM. Maybe it was a sympathetic connection with German rocket scientists?)

A camera box, oddly reminiscent of early 'talking pictures' camera enclosures, was first mocked up from plywood on retired SP 9120 - we presume because SP 9113 was already being stripped and using another chassis was convenient. This design was submitted to the ICC for approval; the intent was to allow the option of Camera Car operation in regular freight service at the point of a locomotive consist.

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

The Camera Car carried sophisticated recording equipment: two custom-built Mitchell 35-millimeter feature film cameras set up for half-frame format, and two Nagra III professional feature film multitrack timecode audio decks, all connected by XLR-type cabling.

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Bogen Audio supplied internal communications equipment, so that the camera crew could converse with the operating crew. A switch panel controlled external lighting from the camera room.

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

There was a steel box fabricated under the Nathan Air Chime horn, built to contain two stereo microphones, keeping them away from wind noise and buffering the high-decibel input level. The horn mount was raised with two solid steel blocks, welded and drilled to clear.

Howard

P. Wise Photo

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Howard

P. Wise Photo

|

Joe

Strapac Collection

|

Observe in the last photo, above, how much the lower edge of the windshield had to be raised to clear the camera enclosure. It's another installment of our favorite game show, "I Never Noticed That".

There were likely several other mic positions to record bell, wheel noise, and perhaps the sounds of the trailing locomotive which actually provided motive power. We're aware of no specifications for these microphone locations on SP 9010.

The remains of a 'mult box' with coaxial cable connections was still in place above the righthand number 2 axle when the unit was acquired in 2008. First appearing in photos around 1973, the red-painted box appears to have been physically connected, through a Barco speed recorder drive head, between the axle journal and the box. By 1979 the box remained cabled to the chassis but had been pulled out of the way, and the axle drive blanked off. We speculate that the box and its drive provided some sort of speed-calibration signal to the onboard recording gear.

Craig

Walker Photo

|

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

Howard

P. Wise Photo

|

In the camera nose, two seats from another retired KM -- SP 9120, perhaps -- served the sound and camera operators. (This choice fortunately provided 9010's restoration with a surplus of these adjustable S. Bremshey & Co. ergometric seat units, much needed because of heavy deterioration of the existing cab seats from exposure. SP crews reportedly claimed a number of these seats from salvage to use on their recreational Bass Boats!)

In the locomotive cab, controls were retained to allow command over a trailing locomotive to supply motive power. Note the long General Electric model U25B-style reverser lever resting on top of the GE-supplied sixteen-notch KC-99 control stand:

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

Back Behind the Cab.

We can confirm: reports of one of SP 8799's Maybach V16s having been removed are incorrect. Both prime movers were retained for weight balance. It was instead -- as the photo comparison below confirms -- the Number 1 radiator room which was evacuated.

SP removed the Behr radiator groups, the transmission heat exchanger for the forward transmission, both German Westinghouse V-6 air compressors and fluid couplings, the Vapor-Watchman engine cooling water preheater, the hydrostatic oil pump which drove the radiator fans and actuated the air motors for the radiator shutters, all three radiator fans with motors, and a few assorted filters and other plumbing.

Top:

Bob Zenk

Bottom: KM Werkfoto |

In the vacated space SP installed an Onan skid-mount diesel generator to power the controls of the car, its lights, and the recording equipment, blanking four sets of hood doors in the process. Fuel was tapped from the original 4200-gallon underframe tank. And the cab controls worked in multiple-unit mode, with a trailing locomotive supplying motive power and traction.

And finally, a large EMD (General Motors)-style wedge snowplow pilot replaced the diminutive KM original. A prodigious welded shelf provided support for the long-shank coupler, and new slots to reposition the multiple-unit connector piping were cut into the pilot sheet's now-beleaguered Austrian steel.

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Phases of the 'Sim'.

Bob Zenk Photo

|

The Camera Car was also called 'The Simulator Car' by some SP employes. And it received running mods almost immediately, piling on the appliances and adding to its profoundly ungainly visage. We're reluctant to succumb to a railfan's and modeler's term and call these modifications 'Phases' -- but let's yield to the temptation as a visual spotting shorthand.

Phase One: February, 1969.

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

The unit rolled out of Sacramento General Shops in February of 1969 being referred to as 'SPMW (Maintenance of Way) number 1', but this may have been unofficial, or simply shop floor shorthand. At this time, the unit displayed no cabside road number, there were no air curtain blowers under the camera port windows, and the unit wore a flush-mount Pyle-National red Gyralite in the boxed spine applied to the nose.

The unit number was identified only by a small stencilled 'SPMW 1166' - signifying that the unit had been initially placed within the existing Maintenance-of-Way roster.

Phase Two: Early 1969.

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

SP

9010 Collection

|

The Gyralite was the first to go. We don't know if the proximity of the mechanism was causing interference with the sensitive camera and audio systems, but it was replaced with a Mars unit mounted at the very top of the nose, externally.

The reason for the move may have been optical. A small notch was cut into the boxed headlight 'spine' near the camera ports - clearly a solution to a problem with vignetting of the film frame.

And also very soon after rollout, the need became apparent for an external air curtain to keep the camera ports clear. (We don't think that the Addams Family's 'Thing' is waving here, but we're not sure.)

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

We learned an amusing story from one of the SP shop employes working on the Camera Car air curtain. We'll let SP 9010's good friend Chuck Drake tell the story:

"While the Southern Pacific had a fine engineering staff in San Francisco, prototype modifications like this were usually detailed in very basic terms for Sacramento. Many items were left for Individuals like (General Foreman) Ron Sixby and shop personnel to work out.

The lens blower was a particularly troublesome item to design. Ron Sixby was a fine man... there was no one within the Mechanical Department who did not admire and respect him.

Chuck

Drake Collection

|

Ron had the boiler shop make several versions, and as each was completed, various flaws would surface. Finally, one looked promising. It was finalized and arrangements was made to test the air flow at various track speeds.

It so happens I turned out to be those arrangements.

I had just bought a new Ford pickup and it was decided to use it for the test. We bolted the blower to a sheet of plywood and proceeded to an abandoned levee road behind the shops. As I would not allow holes to be drilled in my new truck, several bags of sand and Ron were used to anchor the blower to the truck. Ron climbed into the truck with the blower and we agreed on a series if hand signals to regulate the test.

Instructions were that we were to proceed at various speeds while Ron took air flow readings at the blower's output. He would convey the readings to a third individual to record. I was designated driver.

All went well until we reached speeds around 45 mph. The levee road was relatively short and we would run out of room in a short time. Trying to watch both Ron and the road, I would keep one eye on the rear view mirror and the other on the speedometer.

All of a sudden, all I could see in the rear view mirror was Ron's huge behind and the bottom of the plywood sheet that the blower was secured to.

After an emergency stop and a short time to allow Ron to stop bouncing around in the bed of the truck, we decided that the readings thus far taken were acceptable and the test was concluded.

We joked about this for many years. Ron would accuse me of ignoring his hand signals to slow down and I would accuse him of obscuring the rearview mirror with his big rear end."

Phase Three: Mid-Late1969.

Alan

Miller Photo

|

Bob Zenk Photo

|

Bob Zenk Photo

|

Bob Zenk Photo

|

The unit would wear at least three varieties of air curtain blower, of increasing duct size and presumably better air control. Here's the second incarnation, which may be nothing more than a filter shroud around the original blower motor:

We're calling this change in appearance a 'Phase' because at this point -- early Summer of 1969 -- the number 8799 was painted on the cab sides, on the Fireman's side of the nose, and on the rear end, officially consecrating the new number.

(SP 8800 was the earliest-numbered SD45 on the SP roster, and the Simulator was set up to realistically re-create the cab and controls of a unit of this type. Not just roster logic, it was also a bit of theatricality meant to tie the simulator to the real-life experiences of crews. It worked only so far: some trainees called it a 'fake number'.)

Phase Four: 1969-1970.

SP

9010 Collection

|

Another larger shroud now appears around the air curtain blower assembly. A new duct extension beneath the camera ports focuses the airflow, and a drip awning or sunshade now appears over the camera ports. The road number is also applied to the Engineer's side of the nose, since it's quite readily obscured at some angles by the red Mars signal light.

The Camera Car is pictured here with another noteworthy SP sole survivor, SP 4294, the last Cab-Ahead steam locomotive, currenly a star-in-residence at the California State Railroad Museum, Sacramento.

Phase Five: 1970-1985.

SP

9010 Collection

|

SP

9010 Collection

|

The massive new ductwork appearing around the blower motor and camera ports -- for our purposes, determining Phase Five -- must have been successful, since this longest stretch of time resulted in the fewest visible modifications. A growing package of lights dedicated to illuminating the right-of-way also began to sprout; variations on this appearance are numerous, and we'll refrain from calling each one of these adjustments a 'Phase'.

This modification also saw the dual white Gyralite unit mounting extended to clear the boxier blower duct. And the whole face was now painted Scarlet, ending the earlier, perhaps sportier anomaly of Dark Gray headlight housings and MU connector boxes. (The classification light housings apparently still needed a decorator accent.)

The nose also reverted to a single application of the road number, since the former duplicate spot on the Engineer's side was covered by the air curtain shrouding and no longer available real estate.

Operations: The Big Push.

Bob Zenk Photo

|

SP 8799 was operated in periodic filming duty, making repeated runs down the same length of California mainline while shoved from behind by a single road locomotive.

We're unaware of the existence of complete logs for these filming trips, but we do know that the Camera Car captured at least a portion of the Donner Climb out of Colfax, some part of the Altamont line out of Tracy, and Beaumont Hill through Colton and on to Walnut - this latter route used for the first series of training.

Several types of General Motors EMD motive power shoved on 8799's self-aligning draft gear -- from 1500HP cabless booster model F7B, 1750HP model GP9 and 2500HP model GP35, to SP-subsidiary Cotton Belt 3600HP model SD45T-2 "Tunnel Motor" -- this last with a unique cooling system configuration adapted to high-altitude tunnel operation, ironically born of SP's experience with the Krauss-Maffei hydraulics. We're still looking for records showing that 8799 ever ran on the point in regular train service; all photos show only special movements, as in this set of orders from 1969 out of Colfax:

Bob Zenk Collection

|

Bob Zenk Photo

|

Bob Zenk Photo

|

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

Don Bucholtz shares this fine series of photographs of the Tracy operations in 1979:

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

Don

Bucholtz Photo

|

8799 Leaves Home for a Fixed Base.

After a short locomotive lifespan, one spent virtually tethered to Roseville Diesel Shops for maintenance and Sacramento General Shops for heavy rebuilds, Camera Car SP 8799 finally left its adopted home turf.

Following initial shakedowns out of Roseville, the unit was ultimately sent to West Colton. Southern Pacific's new Engine Service Training Center was first sited in a Conductron-managed facility in Downey, CA, but soon moved to a dedicated building in Cerritos. SP 8799 often was parked on a spur near the building.

Inside that facility was a full mockup of an EMD 'Spartan Cab', with full AAR-style engineer control stand, and outward appearances similar to an SD45. Computer controls for the Simulator Operator were behind the 'cab' area. Emblazoned on the number boards above the slightly truncated short hood was the number '8799':

C.

E. Wherry Photo

|

C.

E. Wherry Photo

|

Our friend Charlie Wherry generously shared his recollections of working the Simulator; his accounts were originally posted on Trainorders.com:

"The SP operation used three projectors, although only one (set of images would be seen) at any given time. As the trainee operated the controls of the locomotive and the 'train' began to move, the stepping of the projector would become apparent at very low speeds, although the screen never showed dark. This became less noticeable as the speed of the train increased.

The original training film was of Beaumont Hill. I believe the film began at around Owl, maybe Pershing and went through Colton all the way to Walnut. We'll say that projector 'A' showed this scenario with all green signals. A second film, on projector 'B' was filmed with a yellow flag (but no green flag) and had the signal at El Casco in stop position.

The instructor would pre-select projector 'B' and at the precise frame selected the computer would shut off 'A' and light 'B'. The intention was that the change in film would not be noticeable. Projector 'C' held a rear-end collision scenario with a caboose in the siding at Walnut. That scenario was filmed in reverse with the camera car at point of impact and the the movement moving as quickly as possible away. That one had birds flying backward!

Very few trainees had the time to make it down to Walnut to see the 'C' run, most spending their time trying to master the art of balancing the grade and getting stopped short of the red at El Casco."

Students quickly learned to 'read' the subtle but unintended cues that were a liability of the variations in image between the 'A' and 'B' projectors, also called 'Default' and 'Alternate'. Students became adept at reading slight color shifts in the film, or other little inadvertent clues, and knew when the 'Alternate' projection - a red signal or other impediment requiring action - had just been engaged.

All agreed that the experience was realistic, and that the motion of the hydraulics gave a real sense of feedback on train handling. The visuals also were highly convincing: students occasionally found themselves waving back at 'bystanders' standing at 'trackside', and SP had to formally post a sign reminding enginemen not to spit out the window!

Second Retirement, Second Salvation.

The Camera Car received little or no cosmetic maintenance attention through the years, growing tattered and weatherbeaten. It was activated sporadically until the early 1980s, when the Simulator technology advanced to a laserdisc-based format.

Goodbye, variable film; Hello, seamless digital images.

SP 8799 was donated to the California State Railroad Museum in April of 1986, where it underwent an aborted volunteer attempt at restoration in the early 1990s.

California

State Railroad Musem Collection

|

California

State Railroad Musem Collection

|

California

State Railroad Musem Collection

|

Volunteers detailed a plan to return the unit to original 1964 appearance, and even traveled to Germany to meet with representatives of the manufacturers, but were met with polite declines of assistance and good wishes for success. During the initial assessment process, cab windows were removed, the blank side plates over the vacated Number Two Radiator Room were cut away, the EMD-style snowplow pilot and extended coupler were removed, and - significantly -- the boxy camera nose was torched off and discarded.

Howard

P. Wise Photo

|

Despite the best efforts of CSRM to secure their inactive projects, outside storage meant that vandals, copper thieves, and the elements had free rein over the hulk of the former SP 9010 for more than fifteen years.

The PLA acquired this forlorn one-of-a-kind in the summer of 2008, fully cognizant of the unique historic qualities. But the KMs have always been an acquired taste for American railroaders and fans. Had the camera nose been in place, it might have been again dismissed as a 'white elephant' and left for scrapping.

But PLA member Charles Franz - not yet born when the Camera Car was retired - made a persuasive case for its acquisition and preservation. And Howard Wise, a veteran of several stunning historic locomotive renewals, became Project Lead.

Patrice

Warren Photo

|

With all of the Camera Car legacy gone, the decision was easily made to begin immediate restoration to this forlorn survivor's unique appearance as a brand-new 1964 German locomotive - a pioneering experiment in high horsepower, efficiency, and superior traction.

Howard

P. Wise Photo

|

Current restoration efforts are focused on returning SP 9010 to operation as a 'control cab', with authority over a trailing locomotive -- in the same manner in which the unit last operated as Camera Car 8799.

It's not a matter of simply cleaning things up; much control wiring is missing through conversion or vandalism, and must be replaced. Eventually, should the healthy-seeming rear Maybach be returned to operation, the empty radiator and auxiliaries compartment will have to be re-populated with hydraulic and air equipment. That's Stage Two of the master plan.

Bookmark this page; we'll have updates as we build the files on Camera Car operation and deployment, plus a lot more juicy detail photos. And if you have historic information to share about the Camera Car and its operation, the SP 9010 Project welcomes all to the effort!

Bob Zenk Photo

|

APPENDIX:

The Santa Fe Simulator

Bob Zenk Photo

|

We Are Not Alone.

We've been careful to specify that the SP developed the world's first 'fixed-base' locomotive Simulator. The reason? Competitor Santa Fe fielded a rolling Simulator aboard two railcars at the very same time.

Who was first? Santa Fe claims first stake in the ground.

In fact, after asserting that SP had the 'first' locomotive simulator, we heard from a fellow who begged to differ in the politest of terms -- with a volume of facts to back up his assertion.

Santa Fe and the Similar Simulator.

We'll let our friend Thomas A. Vojir enlighten us about the parallel efforts:

"I joined Singer-Link in June, 1969 (Singer had recently acquired Link Aviation, of Link flight trainer fame). ATSF had already contracted with Link for the LS (Locomotive Simulator) before then, and it was about 80% complete.

My particular assignment was the computer programming for the visual display system; the display control and motion control were pretty much done when I joined the project.

(The Simulator itself) was a self-contained car with three major sections: 1.) the simulator for the instructor and trainee, 2.) the electronics, and 3.) quarters for the resident technician.

It simulated the EMD SD45.

The simulator focused on starting, stopping, operating parameters, and responding to signals (that's where the visual system came in - letting the instructor change the colors of the lights in the scene at will).

The computer was the Honeywell H316, a direct descendent of the DDP-516. (You may have heard of a small system in which the 516 was used - ARPANet, the forerunner of the Internet. The 516 was the first "router".)

Final assembly was done in the car on a siding at the Silver Spring, MD railroad station through 1969 and into 1970.

The 35-millimeter film for the general view out the front window was done by early 1969 -- everyone on the project had seen it in trial runs by the time I joined in June. The filming was done outside Clovis, NM. As I heard it, that section was chosen because it was real simple; nice and flat, not lots of grade crossings; no semaphore signals (so only the light color changed), and so on."

A Pair of Rolling Platforms.

The two units - Santa Fe called them Simulator and Film Car - were photographed while on display in Fresno, CA in early 1971. The Santa Fe's version of a Camera Car was built in 1918 under lot number 4530 by the Pullman Car Company as Business Car 30. Retired from those duties in 1966, its conversion to Film Car 30 was completed in March 1969. The camera position occupies the area of the original open platform. It was renumbered to Film Car 5009 in July of 1970, and finally to Film Car 73 in January of 1973. It was repainted solid dark gray with a silver roof and silver "zebra" stripes.

Simulator Car 5008 was converted from streamlined coach-lounge car ATSF 3179, and was renumbered to Simulator Car 70 in 1973.

Bob Zenk Photo

|

Bob Zenk Photo

|

Bob Zenk Photo

|

Bob Zenk Photo

|

Bob Zenk Photo

|

Systems and Develpment.

Tom says that principal photography for Santa Fe's sim was likely completed before the SP had wrapped their shooting. He describes the system:

"Making the film early was pretty easy -- Link knew all about film-based runs from aircraft landing training: put a camera at the same position as an engineer's eye in an SD45, and run the camera car through the various training scenarios (i.e., at the various target speeds for each type of training run). The visual system did all the adjustments for the trainee running faster or slower than expected during each session.

We had a big public introduction party hosted by the Department of Transportation at Union Station in Washington, DC." Tom noted that the bracing and tie-downs apparent in the photos of ATSF 5008 were to stabilize the car against the simulator's two-axis motion capability: back-to-front and side-to-side. (SP can still lay claim to the six-axis motion common to fixed-base flight sims.)

Tom notes that the ATSF contract was with the Silver Spring, MD base of Singer-Link:

"They did Task Trainers (such as Anti-Submarine Warfare airborne workstations), and they could handle the locomotive controls and displays fine. The Binghamton, NY operation (where I worked) did the full-blown flight simulators with the equations-of-motion, full 6 degree-of-freedom motion, and visuals."

Tom suspects that the SP work may have been similarly distributed between Conductron-Missouri and other sim-tech contractors to the Apollo and Gemini missions:

"Grumman, as the Lunar Module designer, provided the specifications, Conductron did the cabin and instrumentation mock-ups, and Link did the motion and visuals. I worked on the Space Shuttle simulator, and we carried over lots of Link Apollo stuff."

Shared Tech: The Mitchell Camera and Projector.

Whether Link was a player with SP is uncertain, and less likely because of competition with Conductron. But Mitchell Camera obviously contracted with both railroads during the same period, and shared similar technologies:

"The Santa Fe simulator used a Mitchell projector. What an incredible beast. The SP probably used the same (or very similar) model.

Tom describes a significant difference between the SP and Santa Fe projection systems: Santa Fe used a single film and projector, so there was no telltale color shift as with a film change; students theoretically couldn't outsmart the Santa Fe system as easily!

Santa Fe filmed parts of the railroad with color head 'searchlight' signals, not moving semaphores, so that only the illuminated color indication needed to function in the sim:

The Santa Fe Simulator "had separate red, yellow and green spot projectors on X-Y servos. We calibrated each frame of the film to specify the position and apparent size of a signal light (as it came into view and the train passed it) on the frame. Similar to the technique for the visual speed effect, we used key frames and interpolated the light position, size, and apparent brightness.

Prior to or during a training run, the instructor would select the colors to display, and could vary the color changes and timing of the changes at will during an exercise (pre-programmed or manual override).

This was only possible because the Mitchell projector produced a pulse for each frame as it entered the gate. A magnetic strip on the film at the start of the run gave a signal to zero the film counter, and we used the pulses to maintain a frame count.

Cruise Control.

The Mitchell had a completely variable frame rate, from dead stop to full speed (I think double speed - 48 frames per second). Consumer home projectors often used a continuous film-frame motion, and the shutter was used not so much to blank the frame change but to display only an instant of the film, thus appearing as one static image after another.

Pro-level projectors, such as the Mitchell, used a more sophisticated system. A fork entered the film sprocket holes, the shutter blanked the screen, the fork pulled the old frame out of the gate and the new frame in, the shutter opened on the new frame, and the fork retracted. As implied by the slow-motion and single frame capabilities, the shutter didn't run continuously but only when needed for a frame change."

If the film advance was stopped (as the 'train' stopped), why didn't the frame burn up almost immediately, as home movie projectors might?

"I learned that the Mitchell and other high-end projectors used a nifty glass mirror that reflected visible light and passed infrared. The projector bulb faced upward (for best airflow) and the mirror sat at 45 degrees above it. The mirror bounced the visible light to the projector gate, and the infrared passed straight on up and out.

When curious about how much visible light leaked through the mirror, I looked down the vent shaft. The bulb was a glowing pink, not very bright at all, but the blast from the infrared sure hit me fast. I recommend not trying it yourself to check."

Building a Living History.

Tom's detailed recollections of the 'backstage' side of the Santa Fe Simulator are a wonderful interpolation of what likely occurred on the SP side.

Both Simulators can lay claim to being 'first' - through the tecnicality that Santa Fe's was a mobile training system with limited motion simulation, while SP's was fixed-base and multi-axis like aircraft simulators. SP definitely had the more exotic camera platform, and for that we're grateful. We're also grateful for the recollections of people like Tom Vojir, Charlie Wherry, Chuck Drake, and all the other folks who continue to generously add to the history of SP 9010, its lives and lifetimes.

We eagerly solicit the experiences and recollections of anyone working the SP's Simulator on the tech and development side. Our "KM Memories" page is due for expansion!

~ Bob Zenk